When Superintendent Gregory Thornton arrived to take control of Milwaukee Public Schools after the end of the last school year, he started to work on a number of changes. Certainly the most drastic change came almost right away.

In July, MPS adopted a district-wide literacy curriculum to replace the 17 reading programs and 13 reading assessments previously being used in all 184 schools (only a few schools, like the nine Montessoris in the district, are exempt). Teachers were trained in the new curriculum over the summer and it was put in place when students returned on Sept. 1.

You can read the curriculum — which runs hundreds of pages long — to try and determine if it will make a difference. Or you can ask the educators who are implementing and using it every day.

The ones we spoke to said the new program has changed the way they teach. It has encouraged them to be creative and to model good reading behavior for their kids. And they say, they can see a difference already.

Timothy Manley, a K5 teacher at the Milwaukee Academy of Chinese Language, an MPS charter on 24th and Wisconsin, says that the new curriculum — which at his grade level uses a program called “Journeys” — is a marked improvement over the previous Direct Instruction method of teaching reading. In the past, he, like many teachers, taught reading with a scripted plan that offered little leeway for teachers to make the lessons their own and to adapt to children’s needs.

New approaches

“The new reading program has definitely changed my approach to teaching reading,” says Manley. “If there’s a group of kids that’s still struggling with letter names then you can pull them out and work on that, or if there’s a group of kids that needs more of a challenge then the program offers more difficult books and tasks to suit their needs as well. With Direct Instruction everything was scripted, so every day I would come in, read from my script, and be done.”

Now, instead, Manley says the curriculum not only encourages, but also requires him to think more about teaching reading. In the morning, he says, he sets up work stations, readies his new story for the day, assembles the materials and prepares his song of the day, among other tasks.

“It’s a lot more work,” he admits. “But I’m also seeing a lot more progress, and the kids are really enjoying it, so to me it’s definitely worth all the extra effort.”

While spurring teachers to inject life into their lessons, the curriculum makes no bones about how much teaching is expected of them. Most grade levels do 90-minute reading blocks each day. That mandate is also fueling teachers’ creativity by leading them to find ways to bring other subjects into the reading and writing blocks, says 95th Street School principal Kristi Cole.

“There is a clear expectation of the time requirement for reading and other subject areas — 90 minutes for reading, 60 minutes for language arts (writing) and 60 minutes for math,” she says. “Science, social studies, health, art, physical education and music get the rest of the time. Teachers have to be creative in their integration of these subject areas; such as integrating social studies content in language arts, like writing a letter to Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War.”

At Cole’s school, for example, first grade teacher JoyLyn Rehm has learned to make the most of every minute in the school day.

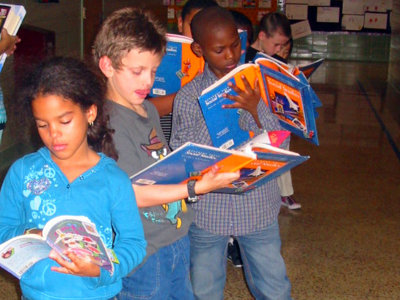

“Ms. Rehm utilizes every moment of instruction time,” says Cole. “Instead of having the students wait in the hallway during the bathroom break with nothing to do — which often takes between 5 and 10 minutes — she has them read.

“This time is a testament to their devotion to reading, although, we do have high expectations for our staff and students at 95th Street School. Teachers are expected to teach and students are expected to learn. There is no time to waste.”

Making reading contagious

Many teachers are also modeling a love of reading to their kids. Four years ago, long before the new curriculum was in place, Samuel Clemens School, on 36th and Hope, began the D.E.A.R. program. Every Wednesday for 15 minutes, everyone Drop(s) Everything and Read(s), including the adults. Now, more than ever, this has proved valuable, says principal Jacqueline Richardson.

“It is important for students to see that our staff values reading,” she says. “For us, the idea is to make reading a natural part of the day, like eating or sharing time with a good friend. We try to incorporate reading in the culture of our school by encouraging students to read every night, on weekends and over long breaks.”

“We strive to get parents to understand the basic idea: If a child sees a parent involved in some activity, the child will want to emulate their parent,” says Hampton’s school secretary Tanya Schmutzler, who helps coordinate the event. “If a child sees mom and dad reading, the child is more likely to pick up a book. Likewise, if it’s an event that involves snuggles and a good story, who wouldn’t want to be enthusiastic and get involved?”

Schmutzler says the program is growing and she’s encouraged because she continues to see new faces at the event. She notes that her school also hosts a monthly Family Gathering Night to ensure parents are tied into their kids’ education. Each evening is focused on a core learning standard, including reading and language arts.

“The goal of the FGN is to increase parental involvement in their child’s education and inform parents of where their child should be academically. The goal is to have at least 25 percent of the student population attend the FGN.”

Ninety-Fifth Street School hosts evenings like “Snuggle Up and Read,” during which parents and K5 kids bring pajamas, sleeping bags and pillows and read together.

“We have classrooms with special reading areas with bean bags, big books, rocking chairs and ‘magic’ readers,” says Cole. “We have Book Buddies, (a program) where older students pair up with younger students and eat lunch together and read.”

Students at the school also keep reading logs as part of their daily homework and get rewards for being good readers,” says Cole, whose school hosts authors to read from their work and invites other guests in to read to students, too.

Manley says that he’s always seeking out new activities and games to tie reading into other subject and into kids’ lives.

“Every week I send home two activities that correspond with what we’re doing in reading for students to do at home with their family,” he says. “In K5 we’ve tried to ‘glam up’ the less popular literacy stations in order to get kids excited about them again. A simple change, like adding ‘reading glasses’ or fun pointers to the library can make a dramatic difference in how the students react to that station … and when we added glitter pens to our vocabulary station is was the most popular place in the room for two weeks straight!”

These activities and others help keep kids focused during a long daily reading block — remember a teacher like Manley is working with 5-year-olds.

A sense of excitement

The curriculum is still in its early days with no results data to track yet, and certainly, with more than 5,000 teachers and principals in the district, not everyone will likely agree on it.

Without speaking on the record, some have intimated that the extra work required by the new curriculum — along with the expected inertia that comes with changing familiar systems — has led to skepticism among some teachers. However, even they are quick to point out that kids have taken to the curriculum quickly and that response has helped bolster support.

There is a definite sense of engagement and excitement — and of progress already — according to the educators I spoke to, none of whom seemed at all leery.

“We are excited about the new curriculum because it … provides students more time on task, differentiated instruction and more non-fiction. It also provides greater continuity of focus at the building and district levels,” says Richardson.

“We do see some real positives about all being on the same page,” adds Cole. “I think the consistency of instruction is clearly a benefit for the school. Also, the literacy centers and varied activities are exciting for students.”

Cole says that as teachers get to know the curriculum even better and spend more time with it, they will continue to create opportunities to integrate it with other subjects throughout the day. She — in a sentiment echoed by Richardson — also believes that a common, district-wide curriculum allows staff within a school — but also staffs at different schools — to exchange strategies and offer support.

“I think it is a positive step forward for our district,” says Cole. “The expectations are clear for everyone and the accountability is there, as well.”

Manley is effusive about the progress he’s seen among his kids so far and he can’t help but compare it to the drudgery of the previous method of teaching reading.

“I absolutely have seen good results from this new program,” he says. “Our 90 minutes of Direct Instruction used to be like pulling teeth every day in kindergarten. The kids hated it and, to be honest, they had good reason to. It was boring, repetitive and just not enough to keep their interest. (Now), the kids can’t wait to get to work. ‘Journeys’ offers really good literature for the children to hear every day, and the flexibility allows me to cater my literacy stations and instruction to the interests and needs of my students.

“They’re already showing a lot of growth and are learning concepts that weren’t addressed until way later in the year with previous reading programs. I’m not the only one seeing their progress, either. The kids themselves are able to recognize their growth and they’re so excited they can hardly wait to volunteer answers or come work with their small groups. This new reading program is more than a positive step forward, it’s a positive leap!”

i evaluate to yes even if there's no image

i evaluate to yes even if there's no image  i evaluate to yes even if there's no image

i evaluate to yes even if there's no image  i evaluate to yes even if there's no image

i evaluate to yes even if there's no image  i evaluate to yes even if there's no image

i evaluate to yes even if there's no image  i evaluate to yes even if there's no image

i evaluate to yes even if there's no image  i evaluate to yes even if there's no image

i evaluate to yes even if there's no image