You can read an endless parade of books about public education. There are surveys of history, books that focus on charters and on voucher programs, volumes devoted to the battles for desegregation and all kinds of books by pundits arguing this or that approach to funding, to curriculum and everything else.

But if you want to know about public education in Milwaukee, start with Barbara Miner’s new “Lessons from the Heartland: A Turbulent Half-Century of Public Education.”

A Milwaukee native, Miner has spent most – though not all – of her life in the city, where her children attended public schools, where she has been associated with Rethinking Schools magazine, where her husband has been a teacher and union leader.

“Half my family are teachers and I told my brother, who is a history teacher in Oconomowoc, that I’m writing the book,” recalls Miner. “This is a guy who reads history books, I don’t read history books. He goes, ‘Oh, MPS history. So, how you gonna keep people from falling asleep?'”

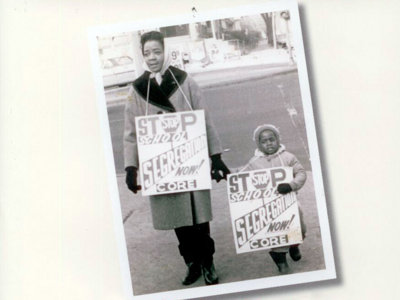

The fact is, Miner’s book is not only a fact-laden history of MPS from the late ’50s forward, but it is an extremely readable book. Blending personal experience, hard facts and Milwaukeeana – like the Braves’ heroic upset of the Yankees in the 1957 World Series – “Lessons from the Heartland” focuses on the big-ticket issues in public schools in Milwaukee and beyond: desegregation, choice and charters.

“I knew I was going to start in the ’50s, you know, post-war Milwaukee, that was it. Things were never going to be the same,” says Miner over coffee at Fuel Cafe one cold Milwaukee morning.

“(MPS’) ‘Our Roots Grow Deep’ book kind of brings you up to the 1950s and ’60s. I knew I didn’t want to go way back (to the 1840s). At some point it just clicked. I was reading the Hank Aaron book where he said, ‘It never got better than Milwaukee in 1957.’ I suddenly went, ‘yeah.'”

The result is a book that focuses on the issues that have fueled crisis and conversation in American public education for half a century by looking hard at schools in our neighborhoods and politicians and community leaders whose names will ring familiar – Maier, Zeidler, Groppi, Norquist, Fuller. While the examples are local, the story is bigger than Brew City.

“It is nominally local,” Miner says of the book, published in hardcover by New York’s The New Press. “But just about everything that’s happened in this district is happening nationwide. It’s so clear that so much of what happened in Milwaukee has had ripple effects nationally.”

Miner says she spent a lot of time on research before ever putting pen to paper.

“I grew up in Milwaukee, so some of these things I felt in my bones,” she says. “But then I left in ’69, came back to Madison in ’73, but left again in ’75. And then came back with my kids in 1985. (I was away from) 1975 to 85, which is the desegregation movement.

“Luckily (husband) Bob (Peterson) is an inveterate compulsive archivist. Our basement is just one file box after another. And Mary Bills, a former school board member, is the same thing. Many people gave me access to files. Before I started writing, I read a lot and I thought, ‘How do I try and make sense of this all?'”

One thing she knew from the start was that “Lessons from the Heartland” – despite its title – would not be a book that offers answers to the problems in education. If any one person had the solutions, the issues would have been eliminated years ago.

“People say, ‘what are your answers?’ I just think we need to talk about this stuff,” she says. “You go back and you look at (the) Groppi (era), they didn’t have the answers. They knew that something was wrong. They talked about it and they made demands. They weren’t afraid to take the powers that be to task.”

The book is garnering good reviews outside Milwaukee.

On his blog, Mike Rose wrote, “One of the admirable characteristics of the book is the way Miner uses the specifics of Milwaukee to illustrate broad natural issues – industrial boom and bust, residential and school segregation, changing ethnic and racial demographics – and their effects on various attempts to reform public schools and/or use the schools to solve larger social problems. … She also knows how to tell a story. The book zips along with one powerful tale after another.”

Publisher’s Weekly boasted, “Intensively, extensively and specifically about the politics of public education in one American city, the issues Miner raises are of great importance to all those concerned with how our society educates its children.”

Here at home, the responses have been similarly positive, but more multifaceted.

“In Milwaukee it’s been, one, ‘this is my life’,” says Miner. “Two, it’s been, ‘it’s about time we started talking. We need a conversation in this city’.”

And among the current teaching force, the book can be a powerful tool.

“New teachers, not only were they not born before Reagan, some weren’t even born before Bush. (I’m) not faulting them for not knowing the history. It’s a cliche, but if you don’t know your history you are doomed to repeat it.”

So, does Miner think we’re doomed to repeat the challenges of the past 60 years?

“I grew up in Milwaukee,” she says, “and I’m always hopeful.”

i evaluate to yes even if there's no image

i evaluate to yes even if there's no image  i evaluate to yes even if there's no image

i evaluate to yes even if there's no image  i evaluate to yes even if there's no image

i evaluate to yes even if there's no image  i evaluate to yes even if there's no image

i evaluate to yes even if there's no image  i evaluate to yes even if there's no image

i evaluate to yes even if there's no image  i evaluate to yes even if there's no image

i evaluate to yes even if there's no image